More from my trip to India…

One of the things I was particularly looking forward to seeing was the Red Fort in Delhi. I am particularly interested in the events of 1857, commonly referred to in England as the Indian Mutiny. My book, Cawnpore, is set during this time and remains, of all my books, my personal favourite. The Red Fort does not feature in the novel, but the Indian forces in Cawnpore (now Kanpur) owed at least nominal loyalty to the Emperor of India in Delhi and his seat was of huge symbolic importance during the uprising. It was also considered, at the time, as one of the most beautiful palaces in the world, so an obvious place to visit.

Arriving at the fort, the first thing that strikes you is that it really is very red (it’s built of red sandstone).

It’s also very, very big. There’s quite a walk along the wall until you get to the impressive Lahori Gate.

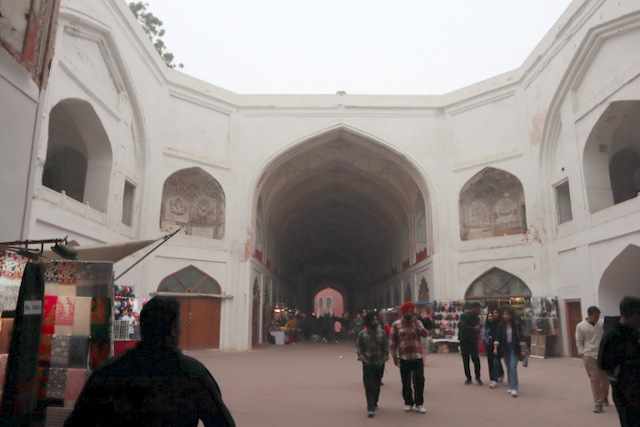

Inside the gate you pass through a bazaar originally built as a private shopping mall for the women of the palace (the 17th century Chhatta Chowk).

Beyond that, though, what you find is a lot of empty space with buildings dotted about here and there.

The first (in line with the entrance) is the drum house. Here, drums above the gate would welcome ambassadors and other dignitaries into the palace. It was also used for reading out proclamations.

The Drum House (Naubat Kahna)

Across a lawn of parched grass, we came next to the Hall of Public Audience.

Beyond that was more parched grass where empty water channels marked the layout of what had once been the spectacular private gardens of the Emperor and, beyond them, a row of marble buildings that had been his apartments.

Stripped of wall hangings, curtains, furniture, and much of their decoration, the apartments are shadows of their former selves, but still give glimpses of the glory that once was.

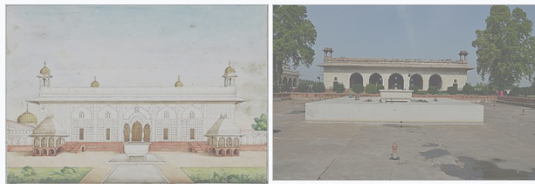

Thanks to Wikipedia, we can compare a photograph of the Rang Mahal (the building on the right of my picture of the row of buildings) taken by Biswarup Ganguly with an 18th century painting of the same structure.

The sad truth is that after the fall of Delhi and the capture of the Emperor by the British, 80% of all the buildings in the fort were destroyed and those that were left were looted, jewelled decorations stolen, gold ripped from walls and ceilings and much of what remained vandalised by soldiers who saw the palace as a symbol of an Indian nationalism that they were determined to destroy. Even at the time, there were those who condemned the destruction of an architectural wonder.

The apartments that remain were spared mainly because they were used as offices and messes by the occupying British troops, but as isolated individual buildings they made little architectural sense. The Drum Tower, for example, used to stand in the middle of a wall that separated the core of the palace from the more public areas. Without the wall, the gate stands strange and alone. (It was used as the quarters of a British staff sergeant.) The harem apartments, which, on their own, took up an area twice the size of any European palace, were completely demolished and replaced by solid blocks of British barracks, some of which still stand. The area is thought to have contained three garden courts and more than a dozen other courts but no plans of the area were made before the British utterly destroyed it. It was a spectacular act of cultural vandalism, leaving the Red Fort just an echo of what was once one of the most beautiful palaces in the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment