Imperial Warriors has recently been re-published by Endeavour Media, who are my publishers. I’m interested in the Gurkhas, so I was happy to pick up a free copy of the book. It was intended as a little light reading in military history but I found myself fascinated by the story it tells and what it says about both the Imperial British past and the modern Army. When I sat down to write a review it ended up rather longer than I had intended – part summary, part critique and part essay. It’s probably rather like the book: worth dipping in and out of and reading the bits that interest you. Hopefully some of it will.

Some history

Tony Gould served with the Gurkhas in Malaya (as it then was) during his National Service. Like many British officers, he fell in love with the Gurkhas and extended his service to stay on and fight with them until his career was cut short by polio. This book starts with a personal account of his time in Malaya, which goes some way to explain his fascination with the Gurkhas before it plunges into a history of Nepal and the tribes that made up the kingdom.

The history is complicated and I must confess that I struggled to follow it. The crucial part, as far as the relationship between Britain and the Gurkhas is concerned, is that border disputes between Nepal and land controlled by the East India Company led to an invasion by the British in 1814. Following a British victory in which the Gurkha troops had distinguished themselves by their bravery the peace treaty allowed the British to recruit volunteers from the Gurkha army into the Indian army. (At the time it was not uncommon for troops in India to transfer their loyalty between rulers.)

By April 1815 a battalion of Gurkha troops was in action on behalf of the British. This battalion eventually became the 1st King George’s Own Gurkha Rifles, the first Gurkha troops formally incorporated into the British forces which they serve to this day.

A little bit of old-fashioned racism

Nepal was a country built on conquest and the conquered people retained their own identities (and their own vassal rulers). The first distinction the British made was between the “real Gorkahs” and the conscripts from the conquered territories. When the British first started to recruit Gurkhas into their service they were explicitly forbidden to recruit “real Gorkhas” on the grounds that people from the conquered tribes were likely to be loyal to their new leaders while the “real Gorkhas” would be less reliable.

This distinction between different Gurkha tribes eventually developed into a classificatory approach to the various tribes of Nepal that many nowadays (the book was first published in 1999) would reject as “race science”. Even Gould complains that the British carried this classification process to an extreme and a reader in 2018 might be uncomfortable with some of it but the differences between the various Gurkha tribes does seem to be important to an understanding of Nepalese history and the relationship between the Gurkhas and British. It can still produce some odd passages though, like these views ascribed to Lieutenant-General Sir George MacMunn:

In sum, the tall and fair-skinned people of the North West were martial; the short and dark South Indians were not. But where does that leave the Gurkhas who were neither tall nor particularly fair?

Gurkhas were covered by an aspect of the martial races theory mentioned by MacMunn – the philosophy of climatic difference, the supposed superiority of temperate zone man over tropical man…

The Gurkha’s Highland credentials, along with his evident military ability, then, gave him his ticket of entry to the exclusive martial races club.

It’s important to make it clear that Gould himself criticises this sort of talk, but there is inevitably a lot of it in the book. On the one hand, I share his admiration for the Gurkhas, but I feel uncomfortable with the idea that these soldiers are especially admirable by virtue of the fact that they are Gurkhas. The notion that ascribing positive characteristics to a particular ethnic group is just as racist as associating negative stereotypes with them can easily become “political correctness gone mad” but the recurring image of plucky little brown men performing extraordinary feats of valour and endurance under the strict but kindly supervision of fine upstanding Brits does begin to jar eventually. The Gurkhas are, indeed, Imperial Warriors and can easily elicit the patronisingly superior attitudes of an imperial age.

A dashed good tale

The book suffers, like many military histories, from a superfluity of anecdote, but the anecdotes are so good it is easy to forgive them. Whether it’s the story of Rifleman Lachhiman Gurung, who, in World War II single-handedly defended his position for four hours against repeated Japanese attacks despite having to fire one-handed having lost the use of an arm early in the action, or the career of Brigadier-General W D Villiers-Stuart who commanded 1/5th Royal Gurkha Rifles, the stories are all well-told and the gallantry described is humbling. The anecdotal approach can interrupt the time-line of the book, though. The British Army often seems to exist out of time anyway (a Guards regiment still dresses formally for black-tie dinners every night, apparently unaware that it is 2019) but the approach of this book can lead the reader from the mid-19th to the late-20th century with dizzying and confusing speed. Perhaps this reflects the actual experience of the Gurkhas. On one page they are invading Tibet in 1903 (very much in the 19th century imperialist tradition) and a few pages later they are fighting in the trenches of the First World War. If the abrupt transition is a jolt to the reader, you can only imagine what it must have been like for them. Unprepared, untrained and unequipped for this totally alien form of warfare their experience was horrendous and their reputation for courage and fighting spirit took a serious dent. By 1915, though, they were already getting the hang of this new form of warfare and by May two NCOs had received IDSMs. (It’s significant that their Distinguished Service Medals were prefixed as “Indian” reflecting the modified form of apartheid then common in the Army.)

Between 1914 and 1918 55,000 Nepalese were recruited to the British forces, a level of recruitment that had a significant effect on Nepalese society. More than a tenth (perhaps as many as a fifth) of the 100,000 Gurkhas mobilised during the war were killed, wounded, or missing in action. One commentator wondered if any country directly involved in the war lost such a high proportion of its fighting men.

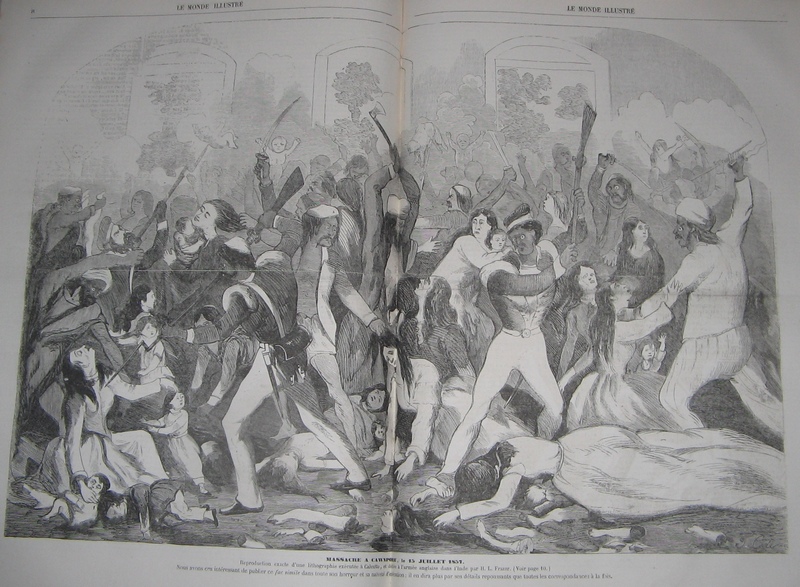

The move to Indian independence

After the war, the Gurkhas found themselves busy with work which was unpleasant in a different way. The move towards independence in India meant that Gurkhas were used as riot police. They were involved in many disturbing incidents of which the most notable was Amritsar. The Gurkhas were not culpable, for they were acting under orders, but the shooting down of civilians was not something that a professional soldier ever enjoys being involved in.

Indian independence, when it came after World War II (where the Gurkhas distinguished themselves in the Far East) was to bring a crisis for the Gurkhas. The Indian government (many of whose members had previously denounced the Gurkhas as imperial mercenaries) now decided that they would be invaluable addition to the new Indian army. The British conceded the principal that around half of the Gurkhas serving under the British flag should transfer to the Indian Army. The mechanics of the process were not well handled. Gould suggests that Indian agents used underhand means to recruit many Gurkhas who would have preferred to serve in the British Army.

Talks on exactly how the Gurkha forces should be divided ran up against the reality of the timetable of partition and, according to Gould, “administrative convenience triumphed over ‘guiding principle’: choosing British Gurkha regiments on the basis of which battalions were stationed in Burma (and were due to leave the now independent country) was the easy option.” Some of the oldest Gurkha regiments found their allegiance transferred from Britain to India with some of the newest regiments put in their places. To a civilian whether your regiment was founded in 1815 or well into the 20th century might hardly be a relevant factor in deciding on operational deployments, but the Army cares about things like this. The casual casting aside of long established regiments with proud traditions (especially those that included the word “Royal” in their title) caused real distress to soldiers and officers alike. The distress was particularly acute for European officers, many of whom were effectively forced out of the Army as the policy of Indianisation took effect.

The End of Empire

Those Gurkha regiments that had transferred to Britain were, in 1948, designated the Brigade of Gurkhas. Ideally it would have been given time to get used to its new situation, but this was not to be the case. From 1948 to 1966 the Gurkha infantry battalions were almost continually engaged in fighting, first in Malaya and then in Borneo. In those 18 years the Brigade of Gurkhas lost 13 British officers and nearly 200 men. Yet the end of the war was followed immediately by cutbacks which saw many of the men sent back to civilian life in Nepal. Conditions for the returning soldier were unlikely to be good as Lieutenant-Colonel Langlands of 2nd Gurkha Rifles explained.

“For the first few months their children could get dysentry, some dying even before they reached their homes. Their small pension or gratuity would not be sufficient to feed them, so they would have to fight to win their food from the soil, and overcome hail, landslides, floods and fire. A few would invest their gratuity in a share of a taxi or a little shop. There were some who had no land to return to and their future was grim.”

Gould is understandably unimpressed by the behaviour of the Ministry of Defence whose civil servants (and those at the Treasury) he clearly considers responsible.

Paradoxically, though the British could be seen as having behaved very badly the sharp decrease in the number of men recruited to the Brigade of Gurkhas greatly increased competition for these places. The desirability of work with the Gurkhas was increased as Gurkha troops were more often serving in Britain where they were paid additional allowances to bring them into line with the British troops they served alongside.

Gould points out that the increased integration with the British Army meant that “improvements in pay and conditions served only to highlight residual inequalities”. This was the start of a campaign for changes in the pay and residency rights of Gurkhas which stretched well beyond the time this book was first published in 1999. The absence of anything bringing the book up-to-date is a definite weakness. Gould understands, as many commentators failed to, that a significant reason why the British employed Gurkhas since the early 19th century is that they were cheaper than British troops. There is a constant tension between the perfectly proper desire of Gurkhas and their supporters to see them employed on the same terms as British troops and the desire of Nepalese Gurkhas who have yet to join the army to continue to have their Brigade of Gurkhas to employ them.

For Gould the return of Hong Kong to China and with it the move of the Brigade of Gurkhas to Britain marked the end of what he calls “the Gurkha world”. The Gurkhas continue to serve, but it is clear that Gould’s love affair is dying. The Gurkhas he formed such an emotional attachment to were those of the 19th century and the world they lived in still survived in the regiments and customs of the Gurkhas he joined in 1957.

The Ghurkas today

Imperial Warriors is, as the title suggests essentially a history book. The Gurkhas he describes are an almost mythic race. Yet I know an officer who, presented with the job that might well be seen as career ending, was convinced that he still had a future with the Army when he was told that he could serve with Gurkhas. The British Army is built on tradition and regimental ties and as the old county regiments are merged or disbanded the Gurkhas maintain a proud tradition of 200 years of service to the British Crown. Gurkha regiments are remarkably effective infantry and as the Army is increasingly plagued by manpower shortages they are likely to have a role for a long time yet. Issues of pay and the treatment given to them when they retire touch many sensitive nerves: our attitudes to immigration; the economics of maintaining an army the country really can’t afford; and the residual racism of both the Army and the British establishment. Gould is not really interested in these issues. The book ends with him returning to Nepal and elegiac account of the countryside and the men who live there. The book is, indeed, a tribute to a world that has gone. It is, for all its rambling and anecdote, a worthwhile and fascinating read but there is another book to be written about the role of the Gurkhas in the modern army. It may not be as exciting and it will almost certainly be shorter, but it is a tale that deserves to be told.

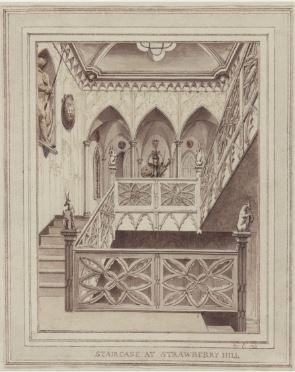

The Castle of Otranto from an illustration in the original book. Rather larger than Strawberry Hill

The Castle of Otranto from an illustration in the original book. Rather larger than Strawberry Hill