Time to put Waterloo behind us and turn to another battle,

later in the 19th century.

A few weeks ago I reviewed Paul Fraser Collard’s novel, ‘The Scarlet Thief’ which tells the story of the Battle of the Alma in the Crimean

War (1854). It’s told from the point of view of Jack Lark, a common soldier,

who has stolen the identity of an officer and now finds himself leading a

company against Russian troops. I looked at some other reviews and saw that

many people were uncomfortable with the central idea that a regular soldier

could pass himself off in this way. It's an interesting question for two

reasons.

Firstly there's the whole issue of how realistic fiction needs to be. I have had criticism of ’The White Rajah’ on the grounds that my narrator, like Paul Collard’s hero, is unrealistic, because an illiterate sailor could not have learned to express himself so well on paper. But both Paul and I are using our character as a sort of "Everyman" to allow more insight into the events they are describing. It's a well-established technique in fiction where, strange to say, not everything the author writes is absolutely true. That, after all, is what fiction is.

Firstly there's the whole issue of how realistic fiction needs to be. I have had criticism of ’The White Rajah’ on the grounds that my narrator, like Paul Collard’s hero, is unrealistic, because an illiterate sailor could not have learned to express himself so well on paper. But both Paul and I are using our character as a sort of "Everyman" to allow more insight into the events they are describing. It's a well-established technique in fiction where, strange to say, not everything the author writes is absolutely true. That, after all, is what fiction is.

Secondly, and rather importantly, it's not always clear that

these "unrealistic" characters are all that unrealistic at all. I had

that problem in ‘Cawnpore’ where my European protagonist disguises himself as

an Indian. It is, as I’ve explained on this blog,

not nearly as unlikely as some critics claim. Today, though, I’m handing over

to Paul Collard to explain why Jack Lark isn't necessarily as unrealistic as

you might think.

The Epaulette Gentry

Jack Lark is an imposter. I make no

bones about it. He steals other lives, taking them as his own, and these

assumed identities plunge him into adventures that he could never have dreamt

of experiencing when he was just an ordinary redcoat serving on garrison duty

in a quiet English town.

To some the

notion of such an imposter is mere twaddle, the premise so wholly unlikely that

Jack’s stories are just not credible. I do not agree with this accusation. For

one, it plays to stereotypes, something that I do not like one bit. It assumes

that all officers of the period were highly educated gentlemen from a world

unrecognisable from that lived in by the men under their command. It also

assumes that the men in the ranks, the fabled British redcoats, were uneducated

brutes, who had no idea how to pass the port, or how to talk about fox hunting,

or any of the other things that a stereotypical upper class officer would

clearly have talked about at all times.

|

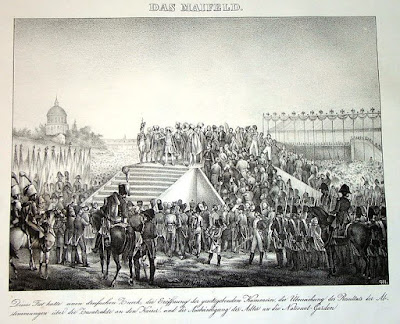

| The Battle of the Alma |

Neither of these

two assumptions is necessarily true. I worked hard on Jack’s story, taking the

time, and thought, to give him the skills he would need to succeed as an

imposter. I am happy to say this part of Jack’s story now forms a central part

of the three short stories that are being published alongside the main series,

and it was a real treat to be able to show more of where my Scarlet Thief came

from.

You see, not

every redcoat was an uneducated ruffian, and rudimentary reading and writing

skills were more common than some may imagine. Around one in six redcoats were

literate, a number shocking by today’s standards, but not perhaps, as scarce as

the stereotype requires. These skills were essential for any redcoat looking to

progress up the ranks, and many regiments actively encouraged their

acquisition. It would be true to say that the education of the men in the ranks

was largely dependant on the mindset of the regiment’s colonel, but many

regiments had libraries, albeit stocked by the colonel himself and likely to

reflect his thoughts on what was suitable for his men. Soldiers deemed worthy

were given the chance to use these facilities to acquire the clerking skills

they would need to progress to a higher rank, but there would often be an older

soldier happy to help in their education that could be as broad as many found

in a school of the period. Many redcoats would have become quite as educated as

their officers.

We should also

consider what manner of man became a British army officer at the time Jack

carries off his scandalous imposture. Would they really be cut from such a

different cloth from the men they commanded, that a ranker pretending to be an

officer would really be as noticeable as a peacock in a henhouse? We must

remember that this is the period where no qualification was required to become

an officer, and there was no formal military training provided outside of that

given by a new officer’s regiment. Quite simply, if you could afford to buy

your first commission then that was deemed the only qualification needed.

It is true that

a number of officers would hail from the upper classes, especially those who

purchased commissions in the fashionable guard and cavalry regiments. But what

about those regiments with a little less dash, those humble line regiments that

came from the counties of Britain? Many of these regiments were officered by

the epaulette gentry; men from respectable enough backgrounds, but for whom

their purchased commission was really their only evidence of belonging to some

notion of gentry. Such men hailed from a world surprisingly close to that

inhabited by some of the men they would command.

I believe that

these younger sons of country squires, clergymen or successful tradesmen, would

not be so vastly different to a man with a keen mind and the brains to use his

time in the regimental library to acquire some degree of learning. In such

company Jack would hardly have stood out, his time as an officer’s orderly

giving him an insight into the officers’ world and the opportunity to learn,

and then ape, their ways.

He is given time

to practice his imposture, the long journey to the Crimea offering him the opportunity

to play his assumed role in the company of his fellow travellers, but not in

the familiar setting of an officer’s mess where perhaps his deception would be

revealed all too quickly. Once in the Crimea, there is little time for any to

doubt him, the start of the campaign against the Russian Empire consuming every

officer’s energy, and surely enough of a distraction to let them put aside any

concerns about a fellow officers manners or accent. In battle, social

distinction means nothing, and Jack’s true talent as an officer comes to the

fore. It is there that he demonstrates the courage and leadership that his men

need so desperately in the maelstrom of battle.

So perhaps he

does stand out after all. He is a fighter and a leader of men, traits rare in

any period of history. His education may be lacking in parts, but he has the

vital ingredients that any officer requires.

For me, and for

my story, that is enough.

Paul Collard

Paul's love of military history started at an early age. A childhood spent watching films like Waterloo and Zulu whilst reading Sharpe, Flashman and the occasional Commando comic, gave him a desire to know more of the men who fought in the great wars of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. At school, Paul was determined to become an officer in the British army and he succeeded in winning an Army Scholarship. However, Paul chose to give up his boyhood ambition and instead went into the finance industry. Paul stills works in the City, and lives with his wife and three children in Kent.

Paul's love of military history started at an early age. A childhood spent watching films like Waterloo and Zulu whilst reading Sharpe, Flashman and the occasional Commando comic, gave him a desire to know more of the men who fought in the great wars of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. At school, Paul was determined to become an officer in the British army and he succeeded in winning an Army Scholarship. However, Paul chose to give up his boyhood ambition and instead went into the finance industry. Paul stills works in the City, and lives with his wife and three children in Kent.

.jpg)